Since March 2023, the Greatland Gold (LSE:GGP) share price has fallen 18%. But it hasn’t always been like this. Over the past five years, stock of the pre-revenue mining exploration company has soared by 250%.

On 22 February, the company released its latest Mineral Resource Estimate (MRE) for Havieron, its flagship gold and copper project, in Western Australia. It claimed the mine contained 8.4Moz AuEq (million ounces of gold equivalent).

In coming up with this figure, the company assumed a gold price of $1,700.

Should you invest £1,000 in Greatland Gold Plc right now?

When investing expert Mark Rogers has a stock tip, it can pay to listen. After all, the flagship Motley Fool Share Advisor newsletter he has run for nearly a decade has provided thousands of paying members with top stock recommendations from the UK and US markets. And right now, Mark thinks there are 6 standout stocks that investors should consider buying. Want to see if Greatland Gold Plc made the list?

If the MRE is correct, it means there’s potentially $14.3bn (£11.3bn) of precious metals ready to be brought to the surface.

Coming back down to earth

But there are reasons to be cautious.

The MRE includes 3.4Moz of ‘inferred’ deposits. These are estimated on the basis of limited geological evidence and sampling.

Also, the company owns only 30% of the mine.

Excluding the more speculative deposits and reflecting the company’s reduced ownership percentage, means Havieron’s metals are potentially worth £2bn to Greatland.

But extracting these from deep underground is an expensive business.

Endeavour Mining, the FTSE 100’s largest gold producer, claims to have achieved an “industry-low” All-In Sustaining Cost of $967 an ounce.

If Greatland matched this, it would cost £1.5bn to extract its share of 5Moz AuEq, giving potential lifetime earnings of £500m.

Including the inferred deposits would increase this figure to £1.2bn.

But these calculations must carry a health warning as they haven’t been discounted to reflect the time value of money.

However, even with these caveats, the mine appears to have a value higher than the company’s current market cap of £330m.

Two charts

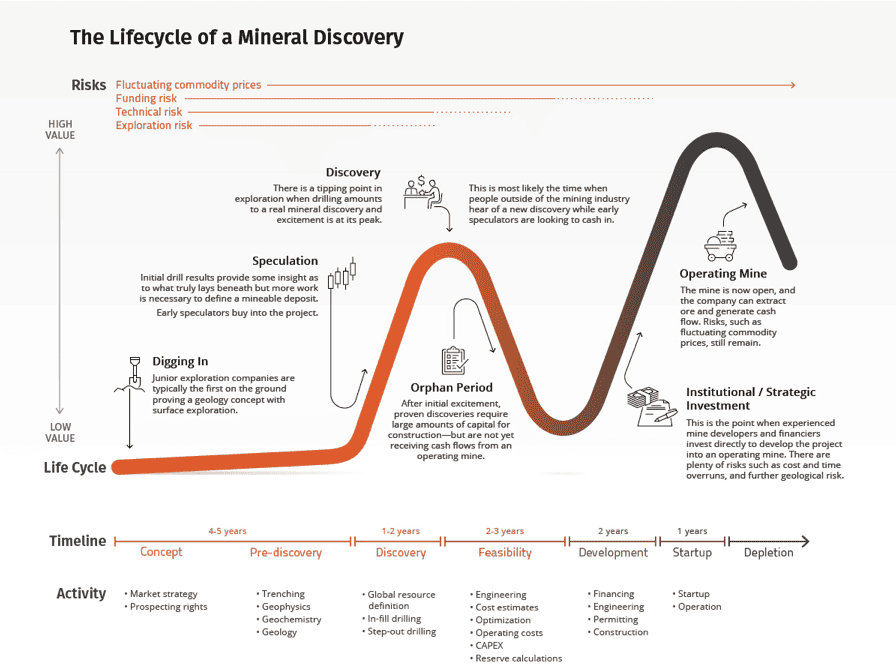

In 1990, Pierre Lassonde published a chart showing the typical life cycle of a mining company.

The Lassonde Curve, which plots a miner’s theoretical value from the concept phase through to production, is illustrated below, along with a five-year price chart for Greatland’s stock.

It appears to me that the latter has — so far — mirrored the Lassonde Curve.

The company is coming to the end of its feasibility stage and now needs to deploy additional capital to develop the mine.

The share price peaked, in December 2020, at 37.35p. It’s now below 7p, which suggests early investors have decided to bank their profits.

But if Lassonde is correct — and the MRE proves to be reliable — the value of Greatland should now increase.

That’s because the company says it has A$220m of committed debt funding from a syndicate of banks, enabling it to start production soon.

And it has other interests in mining projects in Australia that appear to be progressing well.

What next?

I bought shares in the company when they were 76% higher than they are today.

It’s my biggest investment mistake and taught me a valuable lesson.

Early-stage mining companies have the potential for large returns. But to get to the production stage, they need lots of money. And that often means dilution for private investors who are sometimes excluded from the fundraising.

To my detriment, the company now has 33% more shares in issue than when I first invested.

Like Lassonde, I think Greatland’s share price will start to climb as Havieron gets closer to becoming operational, but I doubt it will increase sufficiently for me to get all my money back.